Back to School | The Bare-Minimum Investment Homework

And we’re back! Labor Day is behind us, and everyone is back in their routine. I really hope you got to kick some sand this summer. I know we did, and it was magical. This is THE picture of summer from our end (Courtesy of my daughter who’s making very good use of her new phone by being artistic and creative).

Over the last month, I’ve had conversations with a couple of my close friends’ kids. One is a budding investor who’s almost 13 and making the most of his Greenlight account (not an endorsement, just a fact). The other is a very impressive just-turned 18-year-old who’s off to college and wanted to be in charge of her own money before she set out on the next adventure. (She’s already thinking about grad school, so she’s certainly ahead of where I was when I turned 18.) They both wanted the simplest orientation on investing so they could make decisions that made sense to them on their own.

I have huge empathy for these two. I remember getting my first job “with benefits” (working for Bob Merton in New York City) and getting a 401K election form – it was the mid-2000s and this was a paper form, so any decision felt even more permanent… Imagine the shame of asking for a new form from HR because I messed it up!). I was a Ph.D. student getting a job to build an investment engine with a Nobel-Prize winner and the choices I was faced with literally made no sense to me. Sure, a little small-cap international, and some REIT allocation, and why not throw in a little active commodity fund in there? I mean, literal non-sense! No way to make a rational decision. Screaming “argh” and picking a little of everything, just in case, was probably where this mess landed.

Almost twenty years later, I now know why most of those choices are put in front of you, and it doesn’t mean they all belong in your financial diet. But I’ll forgive anyone for being confused and a little intimidated.

So if someone in your life wants the bare minimum so they can make non-crazy decisions on their own, whether it’s a kid’s investment account or their first 401K plan (hopefully now they get to make their investment elections online), here it is.

There are three fundamental concepts to get your head around. If you get those, you’ve got the real basics.

3 Things You Should Know

What’s a stock? When you own a stock, you own part of a company, but you have professional businesspeople manage it for you. As the owner, you make money if the business does well (it grows and attracts more investors) but you could lose money if the business struggles.

What’s a stock ETFs / mutual fund? You own a lot of companies in one place. It spreads the risk: You are not taking one big chance on one company. You’ll find those ETFs in your investment account and funds in your 401K.

What’s a bond? When you buy a bond, you’re lending money to someone (a government, a company, etc.). They will pay you interest on the loan. You probably won’t make a lot of money, but it tends to be safer than a stock. How safe depends on who you lend to. The US government, very little risk. Some company that borrows a lot could be pretty risky.

Now that you know those three things, we can start putting some structure in place so that you can decide what’s right for you and learn what’s wrong for you along the way.

Decide What’s Right for You

I would go through the following. Now, understand you’re on your own, and therefore this is not financial advice. This is a framework for you to make decisions.

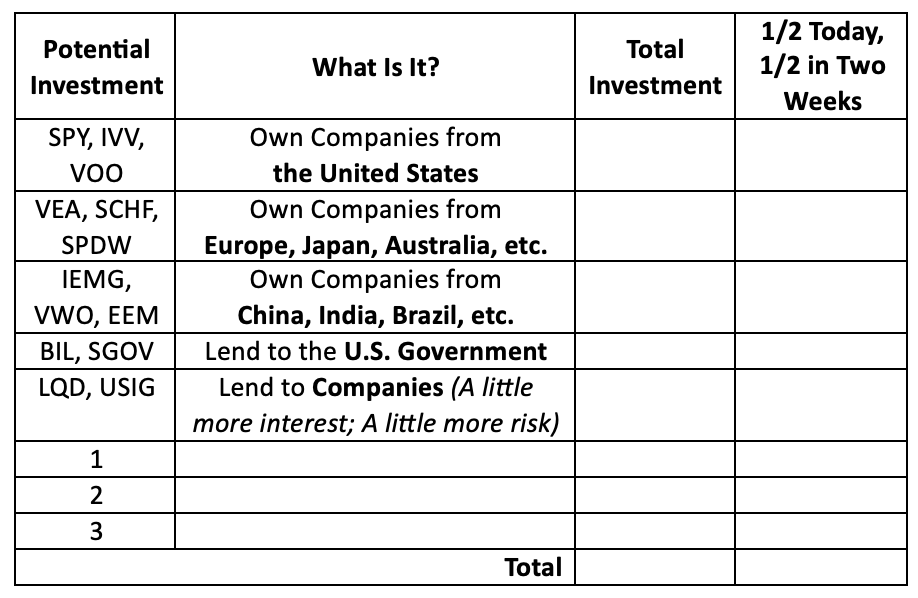

The tickers are the largest three (or two when only two qualify) ETFs by category: Large Capitalization US Stocks, Developed ex US Stocks, Emerging Market Stocks, Treasuries, Investment Grade Bonds.

Decide how much you want to:

Invest in large US companies

Invest in companies from places like Europe, Japan, and Australia (so-called Developed ex-US)

Invest in companies from places like China, India, and Brazil (so-called Emerging Markets)

Lend to the US government with the lowest amount of risk you can come up with

Lend to relatively safe (not perfectly safe) US companies that don’t borrow too much (so-called Investment-Grade companies)

And then, go ahead and pick a few stocks that “you like.” You may do well. It’s totally possible. You may also find out that owning stocks “you like” is a lot to sign up for. It’s a lot of emotional attachment, and there are a lot of ways for that to go badly. A good company may turn out to be a crummy investment. And there is no guarantee that a company you like is even a “good company” in the way professional investors would look at things. To the extent that these are hard and painful lessons to learn, it's probably worth learning them when the stakes are low early in life…

But at least you have a framework to reflect on what’s right for you. Some people — kids included — may find it uncomfortable to put more than a few bucks in companies outside of the US, and some don’t think twice about it. That will tell you a lot about your “Home Bias.” Remember, this is as much about learning about yourself as it is about learning what investing could look like for you.

Oh, One Last Thing

And there is one last piece to this puzzle. See the last column? It says ‘1/2 Today, 1/2 in Two Weeks.’ This is because prices move, and investing in tranches spreads the opportunity to buy at different prices. There is nothing worse (more psychologically painful, that is) than buying what you want to buy in full and then the price drops a bunch the next day. So this is a way to manage the regret of going all-in at one price. Thoughtful investing manages regret because regret is just part of it; you can’t avoid it. A little regret is a good outcome, and it’s much better than having a lot of regret. But stick with the plan and don’t forget to do the second half. Otherwise, you may regret doing that…

Again, this is the bare minimum and doesn’t guarantee success. But at least you’re swimming to shore by doing the above instead of being out there floating around the wreckage of confusion and uncertainty. This is not a complete “system,” for sure. Adding a bunch of extra stuff might feel like a way to “cover the waterfront, just in case,” but some commitment to simplicity is a virtue. That’s because when things go badly, at least you will know what’s doing what and how it should behave. It might even get you to approach volatility from a place of clarity and strength and ask, “what should I buy?” That would be a win relative to saying “get me out of here” at the first sign of discomfort. Did I mention investing is uncomfortable? Yeah, that might be the most important lesson of them all.

Thanks for reading. And please share this with friends and colleagues so they can join the over 1,250 readers who receive these insights directly in their inbox. They can subscribe here: Subscribe to the Newsletter (www.treussard.com/subscribe)

Treussard Capital Management LLC is a registered investment adviser. Information presented is for educational purposes only and does not intend to make an offer or solicitation for the sale or purchase of any specific securities, investments, or investment strategies. Nothing in this writing is investment advice. Investments involve risk and, unless otherwise stated, are not guaranteed. Be sure to first consult with a qualified financial adviser and/or tax professional before implementing any strategy discussed herein. Past performance is not indicative of future performance.