Beyond the Reef

Summary:

Venturing Beyond Familiar Waters: It is worth exploring less familiar asset classes beyond U.S. stocks.

Navigating Home Bias: Recognize home bias in investing, especially when certain asset classes, like municipal bonds for income investors, carry a strong "brand" appeal.

Exercising Caution with “Engineered” Yield: Exercise greater discernment with engineered yield strategies, which often involve selling options, either explicitly or implicitly.

I had the great fortune of attending my daughters’ school-play performances last weekend. The kids put on a very fun and very meaningful rendition of Moana, the story of a spirited Polynesian girl who sails out on a daring mission to save her people. Defying her tribe's ancient prohibition on voyaging beyond the reef, Moana sets sail into the uncharted waters. Along her journey, she encounters Maui, a legendary demigod, and together, they embark on an epic adventure across the vast ocean. Through her quest, Moana discovers her own identity and what it truly means to be a wayfinder.

I’ve been thinking a lot about the idea of sailing “beyond the reef.” Pushing past the comfort of tradition and familiarity to face the unknown in hopes of a better outcome. To me, that feels personal. Before I could become an immigrant to the United States and a proud naturalized US citizen, I had to sail beyond the reef of the world I had grown up in. I remember flying over alone as a 17-year-old and wanting nothing more than for the plane to turn back. I will be forever grateful that it didn’t.

Sailing beyond the reef also has immediate resonance to me when it comes to investing. One of the key findings in the academic literature is that investors display a great deal of “home bias” (Nerd alert: seminal paper here). In other words, investors tend to over-invest in markets that are familiar to them, particularly their local stock market. US investors own too much in US stocks, Japanese investors in Japanese stocks, Europeans in European stocks, etc. That’s not ideal in the most general sense because it prevents investors from being as well diversified as they could be, meaning that their portfolios probably have too much risk in relation to their return potential. That’s not great, but call it “normal not great.”

The real injury (beyond the normal insult) comes when your local market is particularly distorted relative to the norm in terms of valuations and, as that sort of thing happens, a “correction” (read: very bad decline) takes place to force valuations back in line. Look no further than the poor Japanese investor who owned on average 98% Japanese stocks in the late 1980s right before the Japanese stock market crashed by about 75% (and then took 30 years to reclaim its 1989 high). Yikes. But looking beyond your local market might seem like a scary adventure into the unknown. There is a reason the expression “the devil you know” exists. Investing beyond the reef takes what Rob Arnott calls the willingness to take maverick risk, where the predominant risk may not be as much objective as it is psychological. Who wants to potentially face the embarrassment of doing something different and looking silly when everyone else is on the same program? I don’t know, if you ask me, that’s a very human starting place, but humans have also been exploring beyond their comfort zone forever. That’s kind of our thing.

Coconuts — Rich and Cheap

So why explore? The basic argument is diversification. Got it. But what if your particular island — no matter how big and mighty — doesn’t look well-positioned for a bountiful harvest over the next decade? Let’s look at the US overall and large US companies, more specifically. When you compare US stocks to the rest of the world, it’s helpful to look at two things: valuations relative to history, and how cheap or expensive your currency is, also relative to history. Let’s work backwards.

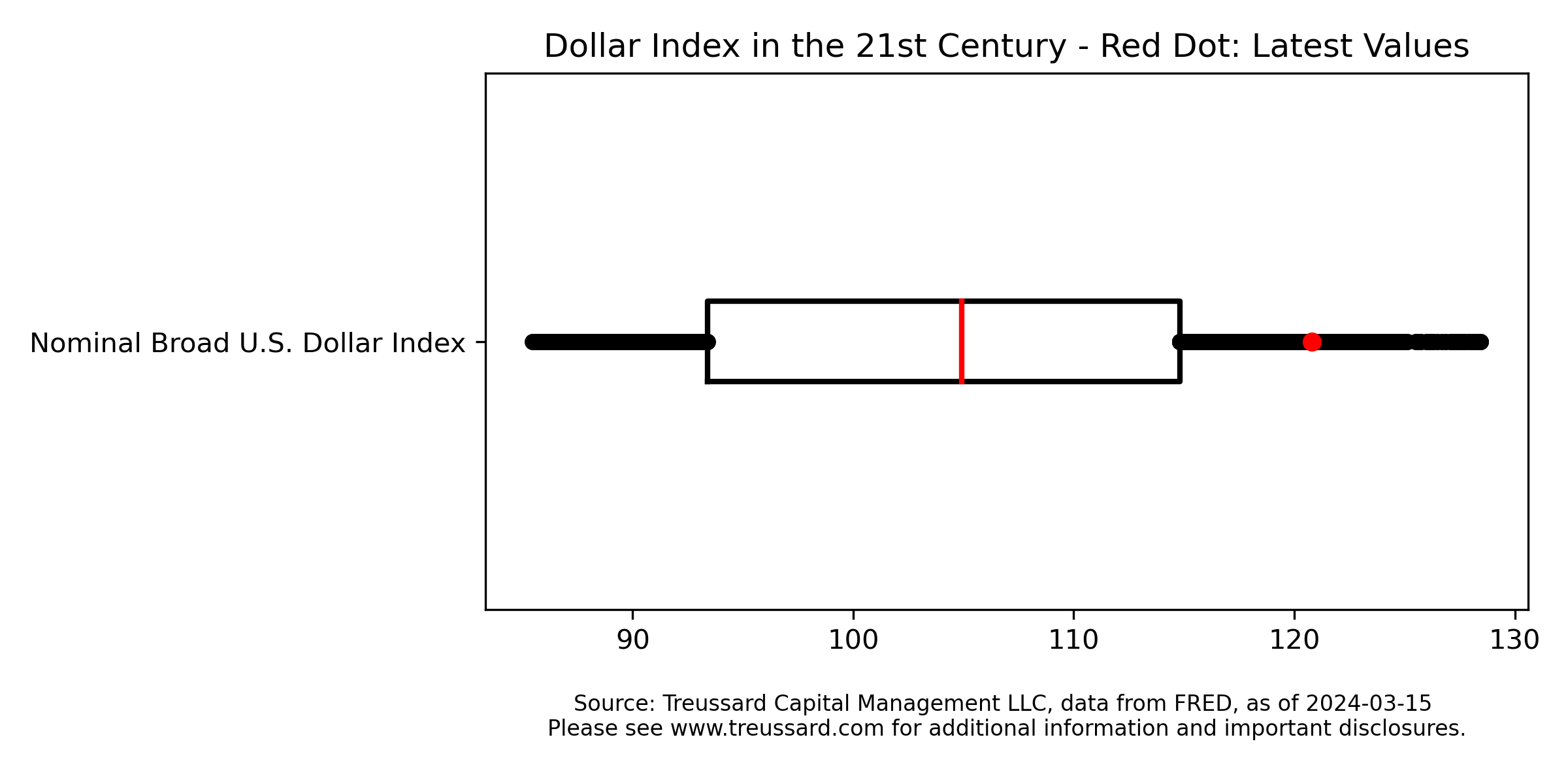

Looking at the US dollar relative to the main currencies it trades against, the US dollar is currently in the 94th percentile of all values going back to 2006 (when the Fed data begin). In other words, the dollar has been this strong or stronger only 6% of all days going back to 2006. And if the dollar gets cheaper (i.e., goes back to a more “normal” range), owning foreign stocks (unhedged for foreign exchange) should benefit from the currency tailwind.

But then, as we’ve discussed recently, large US stocks are not “cheap” from a valuation standpoint. Based on data from my former colleagues at Research Affiliates, US Large companies are in the 97th percentile of valuations going back to 1880. That’s not the highest ever, but it might be too close for comfort. Also high are some of the current darlings outside of the US, such as the Netherlands (91st percentile, thanks for ASML, a computer chip equipment company), Portugal or New Zealand (both in the 85th percentile range… The word might be out that these countries are well positioned for the “US alternative” crowd, but that’s just a guess).

Cheap(ish) are the stock markets of Japan (33rd percentile, but likely close to “normal” given that the data are biased up because of the silly Japanese bubble of the 1980s), Austria, Finland, Sweden, and Germany (all suffering from the “there is a real war going on next door” factor, economically today and from a rational fear standpoint if Russia pushes ahead closer to them). Hong Kong is about as cheap as it’s ever been (5th percentile) but in this case, the real question is whether Hong Kong is still Hong Kong (probably not…) nearly 30 years after the UK handed the territory to China. Cheap for a reason, yes, but that’s how things get cheap.

Home Bias — Income-Investor Edition

Now, there is another form of home bias, which we’ll call sticky-brand home bias. Imagine you’re a self-identified “income investor.” Maybe you’ve made your money and you just don’t want to lose it. Maybe you’re really risk averse and you’re happy with predictable income. The “obvious” answer, based on decades of product positioning and brand association? Municipal bonds, right? We’ve all heard it: low risk, high coupons, mostly tax-free income. That’s nice. But be wary of going to the obvious place where all the other income investors are gathered. Instead do a little “trust but verify” and you’ll find that yes, munis have high coupons — and there are tax reasons for them to be priced above par — but please don’t be confused by the high nominal coupon. Look at yields and you’ll find that today, munis aren’t all that attractive relative to Treasuries, unless you’re willing to lend for the long haul.

Brave New World — A Word of Caution for the Adventurous

As you can tell from the above, I think there is a good argument for leaning into your maverick self, though only to the point of comfort. Indeed, nothing good ever comes out of going too far and cutting bait at the first sign of trouble. That’s how permanent loss of capital happens and that’s the shortest path to what we call “the ultimate failure of decision-making.” But if you’re willing stretch, make sure you stretch for the real thing and please make a distinction between what we can call “natural” yield and “engineered” yield. Natural yield might come from things like high-dividend stocks in Europe. That’s just what these do, what they’re about, and likely to deliver. What you likely won’t get is lots of price appreciation but that’s ok, and to be expected from natural yielders like European utilities or consumer staples.

Engineered yield requires a little more discernment, as the yield is derived from some form of structuring, explicitly or implicitly. Particularly when it’s engineered explicitly, you should worry that someone wants to put that big fat yield in front of you and they hope that you don’t see what the flip side of it is.

A good example is so-called buy-write strategies on US equities (these strategies have been very successful in raising assets through ETFs lately). Buy-write means buying stocks and selling (writing) call options against those stocks. Let me ask you this. Do you really want a lot of equity exposure (where you know, the point is for the stocks to go up) while trimming that exact upside by selling call options? Imagine the following conversation. “Hey, this thing goes up a lot or it goes down a lot. How do you feel about keeping the downside and selling me the upside?” Unless your answer is an immediate no-thank-you, your next question should be, “at what price?” Sadly, current implied volatility is low (29th percentile vs. all data going back to 2000), which means the calls you’re selling are cheap. Think twice about selling cheap options, you’ll thank yourself later.

Here is another one, this one living in the realm of private banks rather than ETFs: Recently, structured notes are being designed to deliver something like 9% unless the market falls by more than 15%, at which point, you the investor get to participate in the downside (i.e., lose money). From an engineering standpoint, it’s a simple Treasury (yielding 5% roughly) and 4% on top coming from the sale of a put option (i.e., market-decline insurance). To each their own, but ask yourself if that is how you want to make your extra yield, by selling insurance to others on stocks being down a whole bunch. Is the extra 4% worth it to you? Maybe, maybe not, that’s a you question. But remember Volmageddon.

On the other hand, there are areas of the markets where option selling is implicit — as opposed to explicit — and it happens to be done at relatively high prices at the moment. One such example is fresh government-backed residential mortgages issued by Fannie Mae, for instance. Unlike stock volatility, bond volatility has been very high. That’s fact number one. Second is to recognize that a government-backed mortgage is functionally like a government bond (think a US Treasury) on which you sold a call option (currently at a decent price) because people will likely refinance if rates go down. In the meantime, you earn that compensation for what is known as prepayment risk. In the world of structured yield, that seems to have more positive attributes — all things equal — than other areas where the marketing department was seemingly put in charge is setting the parameters for a bunch of product engineers. Just sayin’.

Long way around the block to say, if you’re like our dear Moana:

Maybe consider going beyond the reef

Ask yourself whether the coconuts are cheap or expensive

Don’t be too quick to buy coconuts from the farm abutting Mr. Burns’ nuclear plant.

This may help you stay well fed and healthy. Thanks again for reading. I know we pack it in. So thank you! And feedback always welcome.